- Home

- Que Mai Phan Nguyen

The Mountains Sing Page 8

The Mountains Sing Read online

Page 8

My mother looked her old self when she sat in a stream of sunlight, tilting her head forward. She scooped up the mixed bồ kết stew, letting it run through her hair. A river of light wove its way down a river of black.

Enthralled by the scene, I was stunned when her sobs came, so suddenly and unexpectedly. Her hands clutched her shoulders. She rolled into a ball on the floor, her body shaking.

My fingernails dug into my palms. I didn’t care what war meant. I just wanted it to return my mother to me, give me back my father and my uncles, and make our family whole again.

The Great Hunger

Nghệ An, 1942–1948

Guava, tell me how you like this short poem.

Quiet pond

a frog leaps into

the sound of water

You think it’s beautiful? I do, too. The poem is a haiku written by a famous Japanese poet named Matsuo Bashō, who lived in the sixteenth century. I found Mr. Bashō’s poems a few years ago, when I’d become a teacher and decided to learn about the Japanese. I wanted to understand why Japanese soldiers had done what they did in our country. The books I read told me that many Japanese are Buddhists like us. They worship their ancestors and love their families. Like us, they like to cook and eat, and dance, and sing.

Before I read those books, I’d watched the Japanese man—Black Eye—in the winter of 1942. I’d tried to believe that he had some goodness inside of him and that he would let my father go.

Do you really want to know what happened to your great-grandpa? All right. Hold my hand as I go on.

Black Eye advanced. He reached into the cart, and flung a sack of potatoes onto the road. The soldiers kicked open the sack, chopped the potatoes into pieces. I watched my father closely as he put the wooden board back onto the cart. Oh, I watched him—the tanned hands that had held me against his chin, the eyes that had lit up whenever they saw my smile, the lips that had told me countless legends and fairy tales of my village.

Several men from the two groups of soldiers were talking to each other in a language I couldn’t understand. It sounded soft and lyrical. Surely, the people who held such a language on their tongues couldn’t be brutal toward others.

The women were pushed forward. They scrambled frantically into the cart like mice being chased into a hole, hurried by the glinting bayonets. My father stood by, helping them up, sorrow heavy on his face.

“Tell me who the potatoes are really for?” Black Eye roared, shoving his hand against my father’s chest, pushing him away from the cart. “For the Việt Minh guerrillas who just killed my comrades?”

“No, Sir. They’re for my customers in Hà Nội.”

“Ah, for the French, the invaders of your country?” Black Eye laughed. He turned as if about to walk away. But in a swift movement, he spun around, his sword cutting a deadly arc across the air. “Traitor!”

I stood frozen as fountains of blood spouted out of my father’s neck. His head thumped down the road, rolling, his eyes wide with terror. As Công pressed his palm tight against my mouth, my father’s arms writhed in the air. His body crumpled.

The world around me spun as I tried to run toward my father. Công held me back, whispering that the Japanese would kill us.

I looked on helplessly as a Japanese soldier jumped onto the front of the cart, turning it around. He lifted his feet, kicking the rumps of the buffaloes. The cart’s wheels rolled over the headless body of my beloved father.

Oh, Guava, I’m sorry for the tears you’re shedding for your great-grandpa. I’m sorry. I’m so sorry. . . .

I didn’t want to tell you about his death, but you and I have seen enough death and violence to know that there’s only one way we can talk about wars: honestly. Only through honesty can we learn about the truth.

In seeking the truth about the Japanese, I read as much as I could about them. I found out that, during World War II, Japanese troops beat, hurt, and murdered thousands and thousands of people across Asia.

The more I read, the more I became afraid of wars. Wars have the power to turn graceful and cultured people into monsters.

My father was unlucky to meet one of those monsters. He died so that Công and I could live on. He died protecting us.

We brought my father home. My mother leaned against me as we knelt by his coffin, our heads white with funeral bands. The đàn nhị two-string instrument wailed in Công’s hands. He played for the entire three days and nights of mourning, the days and nights that saw our home packed with people who came to pay respect to my father. Only then did I learn how many people he’d helped.

I didn’t want to say good-bye but the time came. The đàn nhị music led the funeral procession to the rice fields where my father was laid to rest. Công played until a dune of soil covered the coffin, the last incense burned out, and the sun died on the horizon.

Công didn’t utter a single word during the entire funeral, but when he returned home, he stood in the front yard, the đàn nhị raised high above his head. His scream tore into the night as he shattered the instrument onto the brick floor. His wife, Trinh, and Mrs. Tú gathered the broken pieces, trying to put them back together, but he would never play again.

I blamed myself for my father’s death. If I hadn’t been driving the cart, we would have gone faster, and my father wouldn’t have met Black Eye. Your grandpa Hùng didn’t let me succumb to my sorrow. “It was not your fault, you were just helping Papa,” he said. “Besides, he wouldn’t want you to be sad. He would want you to celebrate his life.”

My mother was like a tree uprooted. She would just sit there on the phản, her gaze distant and empty. Minh, Ngọc, and Đạt didn’t leave her alone, though. They surrounded her, becoming the soil of her life, demanding that she grow new roots. “Grandma, play with us,” they said, pulling her arms, leading her out of the house and into their childhood games.

We told each other not to venture out of our village. We had to stay away from the fighting among the Việt Minh, the French, and the Japanese, which was growing more intense. We’d hoped for the First Indochina War to end, but it was escalating. Three years after my father’s death, the war found us at our home.

This time, the war came in the form of Nạn đói năm Ất Dậu—the Great Famine of 1945—which killed two million of our countrymen. Rather than being a vicious tiger gobbling us down, the hunger was a python that squeezed out our energy, until there was nothing left of us except skin and bones.

By April 1945, I was so weak that I didn’t care whether I lived or died.

“Diệu Lan, wake up, Diệu Lan!” One morning, I heard Mrs. Tú’s call. I wished the housekeeper would leave me alone. But then, a sound made me open my eyes.

It was the faint cries of your mother. A five-year-old baby then, Ngọc was resting her head on my stomach. Next to her, your uncle Đạt, barely four, lay silent. Your uncle Minh called me. I slowly turned and gazed at him: a hollowed face, dark rings around sunken, yellowish eyes; he was a seven-year-old skeleton.

I sobbed, gathering the children into my arms.

“Mama, I’m so hungry,” Minh whimpered.

Mrs. Tú held out a bowl. Steam rose from her hands but no smell of food.

“Banana roots, perhaps the last ones your mother and I could find,” she said. Her skinny arms trembled and I knew she, too, was starving.

I scooped up the black stew, blowing it to cool, feeding the children, and when they’d had enough, I shared the rest with Mrs. Tú. The banana roots tasted bland in my mouth, but I was grateful for each bite.

As Mrs. Tú lay down, lulling the children to sleep, I looked at what remained of our house. In my brother’s room, an old blanket had been folded neatly and piled on top of two worn pillows. Above a cracked cabinet, the đàn nhị poked out its broken pieces. I wondered whether our lives would stay like the instrument, shattered and unable to sing. The living room was barren, except for a makeshift bench. What had the Japanese done to our furniture? They’d invade

d our village, calling us sympathizers of the Việt Minh. They beat up people for no reason, taking away everything of value: money, jewelry, furniture, pigs, cows, buffaloes, chickens. They robbed us of all our food. They made all villagers uproot our rice and crops, to grow jute and cotton for them. Our family could no longer pay our workers. All around my village, people had gone crazy with hunger. The last drops of water had been scooped out of ponds to catch any remaining fish and snails. No insect could escape human hands. Edible plants were dug up for their trunks, leaves, and roots. It didn’t help that a terrible drought had ravaged our whole region, sucking our fields and creeks dry.

My dear husband wasn’t home. His mother had died from starvation. His father was growing weak but refused to come and stay with us, believing that his wife’s soul still lingered at home and needed company. Hùng had told me he hoped to find something to eat on the way to his father, but I didn’t know what. There was no food for sale at the market. Nobody had anything left to sell.

We’d longed for food to reach us from the south, but nothing. Japan and America had been fighting in other parts of the world, and now American bombs had exploded onto our land, destroying shipping lines, ports, roads, and railways.

I had to do something to keep my babies alive.

In the garden, naked of greenery, my mother squatted on bleached soil, poking a stick into the earth. I staggered toward her. “Mama, where are Brother Công and Sister Trinh?”

She lifted her haggard face. Most of her hair had turned white, thinning on her skull. “They went to the fields.”

I thought about the cracked fields and hundreds of hungry villagers out there, searching.

“Have you eaten yet, Mama?”

“Yes, banana roots.”

Picking up a stick, I started digging with her. Dry soil pushed back against my hands. Surely a manioc or sweet potato was hiding somewhere. This part of the garden used to teem with those plump roots.

After a long while, my mother said, “We have to go look for food.”

“But where, Mama?”

“The forest. There’ll be wild fruits and insects.”

“But that’s too far away.”

“Fifteen kilometers, maybe.”

“It takes three hours at least. I’m not sure we can make it.”

“Listen, Diệu Lan. Every patch of earth close by has been dug up. We must go further. Còn nước còn tát.” While there’s still water, we will scoop. “The forest is our remaining hope.”

“I’ll go, Mama. You stay here—”

“No! We’ll go together.” My mother clutched my shoulder. “Without food, the children will die. They’ll die, don’t you understand?”

In the kitchen, I filled a bamboo pipe with water, looping its string around my shoulder, then picked up a chopping knife. Reaching for two nón lá, I put one on my head and gave the other to my mother.

We unlocked our gate, stepped out and secured it again. A horrific stench made me gag. Nearby, a rotting corpse lay face down on the dirt road, green flies buzzing around it. A bit further on, the body of a mother embraced her baby in their death. Several corpses were scattered in the basin of our dried-up village pond.

“Madam Trần. Help us!” A desperate call rang out from a pile of corpses. A woman with bleeding lips stretched out her palm. On her bare chest lay a boy—a skeleton of skin and bones.

“I have no food left.” My mother bent down, tears trickling down her face.

“So hungry,” the woman whimpered, pulling herself and her son closer to us.

“We only have water.” I lifted the bamboo pipe. The woman swallowed in big gulps.

As I nursed water into the boy’s mouth, my children’s faces flickered in my mind. We needed to hurry and get back to them.

My mother had squatted down, howling. In front of her was the body of Mr. Tiến, who’d worked for us for many years. His wife and son were next to him, their heads on his chest. They died a horrific death, pain still spilling from their gaping mouths.

I pulled my mother up and away. There were people everywhere, lying by the roadside, dying, begging. A few tried to snatch our legs as we wobbled past them, but they were too weak to hold on.

Except for the feeble sounds of humans, the village was quiet. There were no animals left to make a noise. Everything was brown and bleached. Even the landscape was dying.

“Don’t stop anymore, Mama.” I pulled her away as a woman tried to hold on to her feet.

“Give her some water.”

“We don’t have much, Mama.”

“Damn it. Give it to her!”

I eased the liquid into the woman’s mouth. She nodded her thanks, closing her eyes, resting her face on the sun-scorched soil.

We tried to walk faster, passing huts filled with murmurs of children, passing piles of rotting bodies, passing hands that reached out to us, trembling in their calling. We swallowed our tears and walked as if we were blind, as if we had hearts of stone.

Holding on to each other, we wobbled together toward Nam Đàn forest. Thoughts about Minh, Đạt, and Ngọc gave me strength. But the farther we walked, the weaker I felt. My mother was slower and slower with each step. The sun beat down on us, blanching the surroundings into a blur.

Yet we walked. We walked, leaning on each other. We walked, muttering to each other that we had to make it, to bring food back for the children.

Exhausted, I led my mother over to a large tree, barren of leaves. We took off our hats, letting the brown trunk receive our tired backs.

Using the knife, I dug. The earth was as hard as rock. All I could find were some grass roots. I handed them to my mother, who wiped them clean. She ate a few and gave me the rest. With the bitterness of the roots between my jaws, I eyed the horizon, where trees layered into a velvet of green. Hidden inside that greenness could be our saviors: grasshoppers, crickets, sim berries, and mountain guavas.

“Mama, wait for me here. I’ll come back with something to eat.”

My mother shook her head. “Since your father’s death, I can’t be the one who stays behind. If death comes, it’ll have to take me first.”

“It was not your fault, Mama! It was mine. If it weren’t for me, we wouldn’t have encountered those murderers. I slowed us down by driving the cart.”

“No, Diệu Lan. Your father wouldn’t want you to think that way. He loved you more than his life.”

“You’re more than life to him, too, Mama. Stop blaming yourself, please.”

My mother bent her head. “I have something to show you.” Her hands trembled as she unhooked the safety pin that closed her pocket.

I blinked, thinking that hunger must be making me hallucinate. In my mother’s palm was the Trần’s family treasure—a large ruby framed by solid gold and fixed to a gold chain.

“I managed to hide it from the Japanese.” My mother handed it to me.

I cupped the precious item of jewelry to my face, hearing my ancestors’ lullabies echoing from it. My father had received the necklace from his parents. He’d proudly shown it to Công and me. Guava, the necklace had enchanted me so much that I had named your mother—my first daughter—Ngọc, which means ruby.

“Diệu Lan.” My mother swallowed hard. “I’d promised your father I’d safeguard this, to be able to pass it on to you and your brother. But now . . . if somebody offers some food. . . .”

I nodded, returning the necklace to my mother, who carefully put it back into her pocket, securing it with the safety pin.

Holding on to each other, we dragged our aching bones toward the forest. It looked close but was an ocean away from us. We’d left our wooden clogs somewhere along the road, for they’d become too heavy, and now sharp stones dug into our naked feet.

Just when I thought I’d collapse and die, swaying trees welcomed me into their arms.

I broke away from my mother, rushing onto a worn path that zigzagged through the forest. But instead of finding joy, I found more corps

es, of children, women, and men. All around them, fruit trees had been cut down or uprooted. No sight of birds, fruit, flowers, or butterflies. No sound except flies’ buzzing.

My mother pulled my arm, leading me deeper into the forest. In front of a large, thorny bush, she bent down, pushing away low branches.

A narrow opening.

“A path, created by your father.” My mother’s lips curled into a rare smile. In his final years, my father used to take my mother here for a walk, just the two of them. They’d come home with nuts and mushrooms, wild hens, and once, a wild pig.

We put aside our nón lá hats, pressed our stomachs against the ground, and wriggled our way through. On the other side was a tiny path, almost hidden among the trees.

I opened my eyes wide, seeking food. Only tree roots and fallen branches met my gaze. Other people had been there, before us.

“Go deeper, go on.” My mother led me through a maze of passages. Finding nothing to eat still, we walked further and further. My feet trembled under me, but my mother kept forcing the way forward, as if she had gained new strength. We journeyed so deep into the belly of the forest that I no longer knew where we were.

“Will you find the way back, Mama?” I panted, staring at a dense bush we’d just crawled through.

My mother didn’t answer. She walked to a green wall in front of us. It looked thick, woven by intertwining jungle vines.

“There used to be a corn field . . . behind this.” She coughed, pushing the vines away, trying to take a peek, but the wall was too thick.

“Why didn’t you tell us earlier, Mama?”

“I was sure I wouldn’t remember the way.” She clutched her stomach, squatting down. “Perhaps nothing grows there anymore. Perhaps . . . perhaps other people have found it.”

I listened to sounds from the other side. Was that a bird singing? If there were birds, there must be food.

I handed my mother the pipe, telling her to drink. There was only a mouthful of water left, and I wanted her to have it. Holding up the knife, I thrashed at the green wall. The knife sprang back at me, narrowly missing my face.

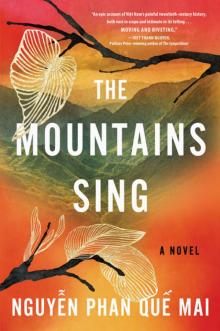

The Mountains Sing

The Mountains Sing